-In order to keep living in popular cities affordable, we need to live more compactly and smarter, and not to see sharing of functions as a shortage, but as an added value for the individual home-

One of the qualities of the profession of an architect is that you may crawl into your client’s skin. To design a good restaurant you need to be a cook, a kind of professional voyeurism. The interesting thing of designing a residential building is that you are both designer and expert at the same time. After all you have been ‘living’ your entire life.

When we were asked to think about a complex of small apartments, my thoughts immediately returned to an earlier Tokyo experience where I lived for two years. For the first few months, I lived in a spacious room in a quiet suburb two hours by train from the city centre. After six months, my girlfriend and I decided to leave our individual apartments and live together in a small apartment in the city centre. It was a conscious choice for us to live in small space in a big city than to live spacious in a small village.

Every time I look back to the floor plan of the apartment, the door seems to be too big. Nothing is less true, the apartment was that small: 18 m2. The apartment was nevertheless the place to live, to sleep, to give parties, but it also served as an office and guesthouse for visits from the Netherlands.

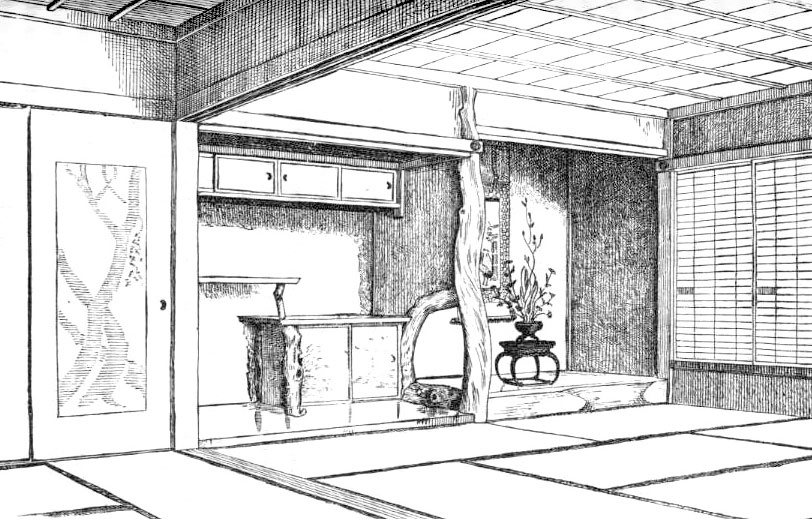

In Japan, I learned that a well designed small space that can assume multiple functions is more valuable than a big space that is not good for anything. To give a small space a high quality, we need to design more than the walls, the ceiling and a few windows as an architect. We have to continue designing. The interior has to become an integral part of architecture. A nice example of this is the Tokonoma, a built-in closet with an elevated stage in the heart of the house, where the resident can put a vase of flowers, a candle or incense. To let the resident’s character speak, all specific possessions are placed on a pedestal. The kitchen, closet and bed are hidden. There is a clear separation between served and serving spaces.

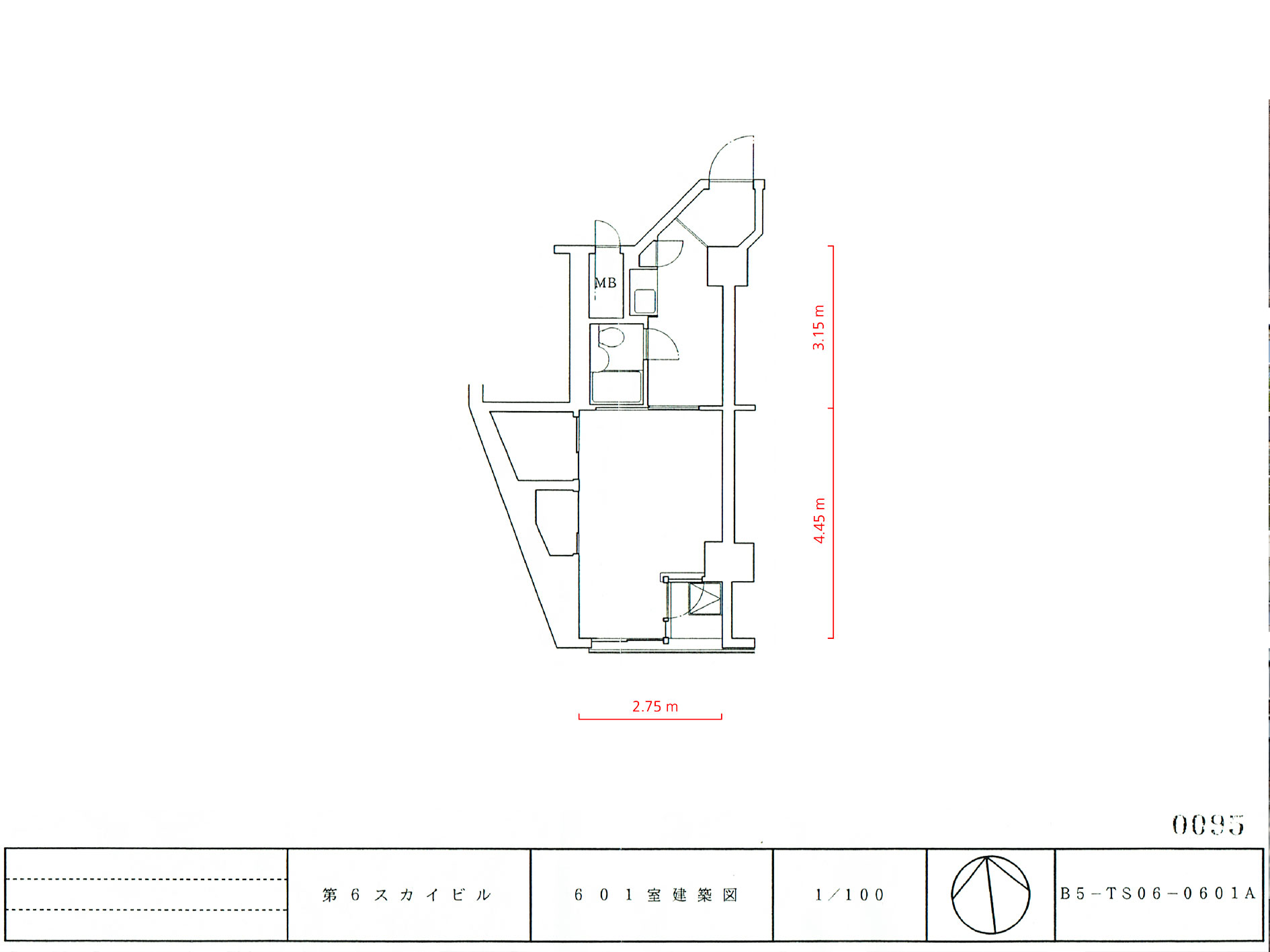

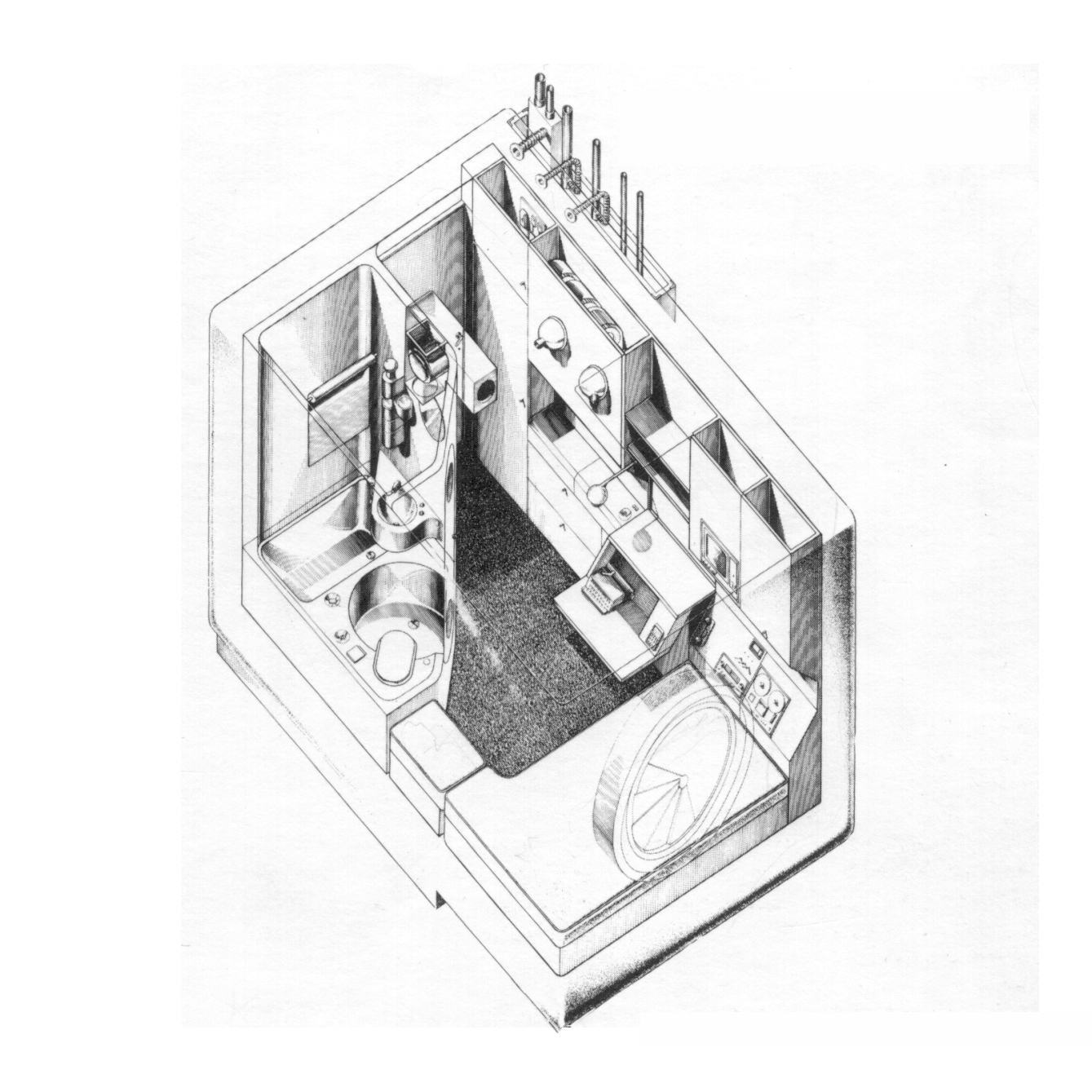

One best examples of this way of designing is the Nakagin Capsule Tower of architect Kisho Kurokawa in Tokyo, built in 1972. Each apartment is a prefabricated steel capsule with an internal size of 2.3 x 3.8 x 2.1m, complete with all built-in home appliances and furniture. The building’s 140 capsules are attached to two concrete cores with just four bolts and appear to grow like branches on a tree.

Nakagin is a constructed manifesto by Kurokawa that brings together many of his ideas. For example, his idea of the ‘Homo Movens’, the nomadic man, in which the individual would play a greater role in society than the family. But above all, the ideas of Metabolism, of which Kurokawa was one of the founders, are easy to read. The Metabolists focused on incorporating the biological idea of growth, change and replacement in the built environment. The lightweight suspension would make the capsules easy to remove and replace.

Nakagin is a celebration of the individual. Two Portuguese architects who lived in the tower described their experience as follows: “We rarely see any of our neighbours, and despite having lived here for a few months, we’ve never come across anyone in the elevator… We have the impression that no one else lives in the building.” Despite the fact that the capsules are now mainly used as offices, no thought seems to have been given to what brings all these individuals together on their shared piece of land of 430m2 in Tokyo, or what their collective potential could be. There is a supermarket on the ground floor, and a generic office floor on the first floor. Only the entrance hall is a communal space. The condition of the tower is now so bad that the hot water has failed, so a temporary collective shower has been created in the parking lot in front of the tower where people can sign up for 30 minutes of hot water. At least one shared function…

The tower is a celebration of the individual and lacks a thought that Kurukawa would develop years later in his book Kyosei no Shiso (English: Each One a Hero, The Philosophy of Symbiosis) where he deals with the concept of symbiosis. In Greek, symbiosis means ‘interdependence’ and refers to a relationship between two different organisms that are beneficial or even necessary to each other.

Symbiosis is a radical different concept than harmony which is about mutual equivalence but also of mutual independence. Symbiosis emphasizes the differences between organisms and the dependence on each other. Think of the buffalo and the buffalo and oxpeckers. Kurokawa argues that differences, discussions between people and because of that an understanding for each other is necessary for connection. Symbiosis would therefore be the best form of society. In light of the latest political developments, I think Kurokawa made a predictive statement in his book from 1991.

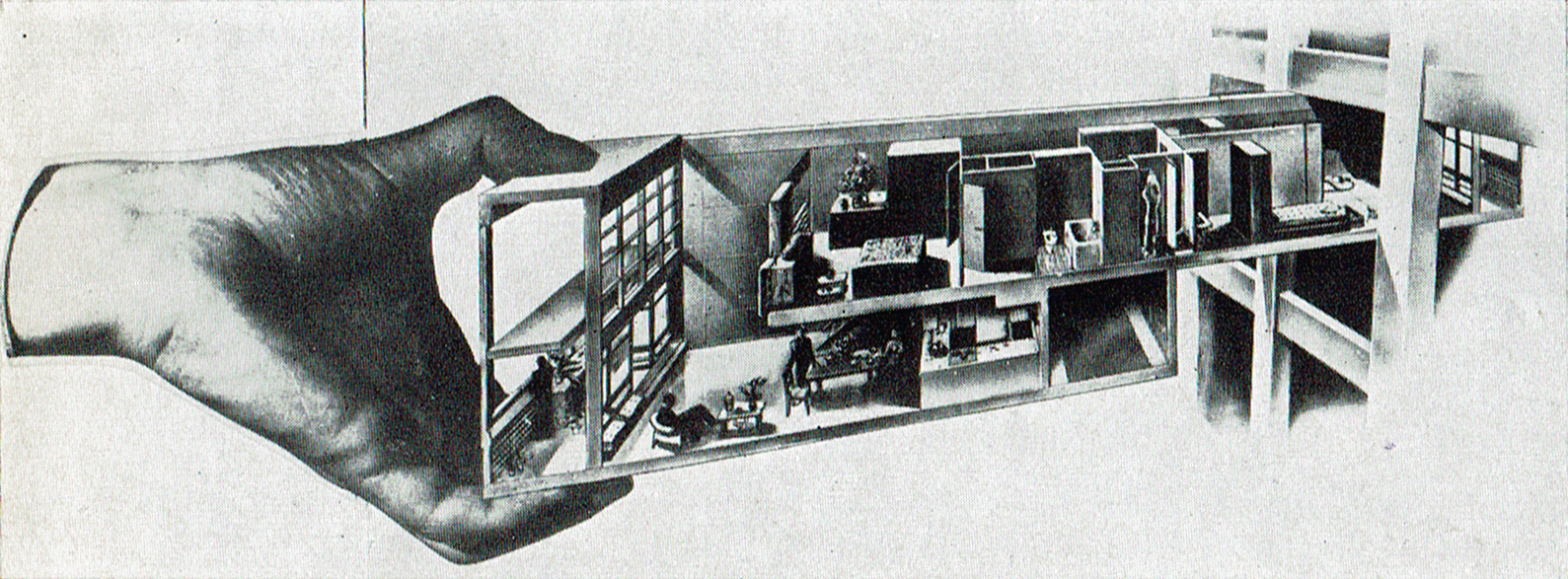

Another iconic housing project of the 20th century that to me embodies this symbiosis, is the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille by Le Corbusier. The building, designed to accommodate and connect different lifestyles and completed in 1952, contains 337 apartments with possibly 23 different typologies ranging from 1-room apartments to homes for families with 4 children. What is interesting about the apartments is that Le Corbusier would have preferred to see them designed as bottles and the structure of the building as a wine rack. Each apartment would be completely prefabricated and lifted into the structure of the building. A prelude to Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower.

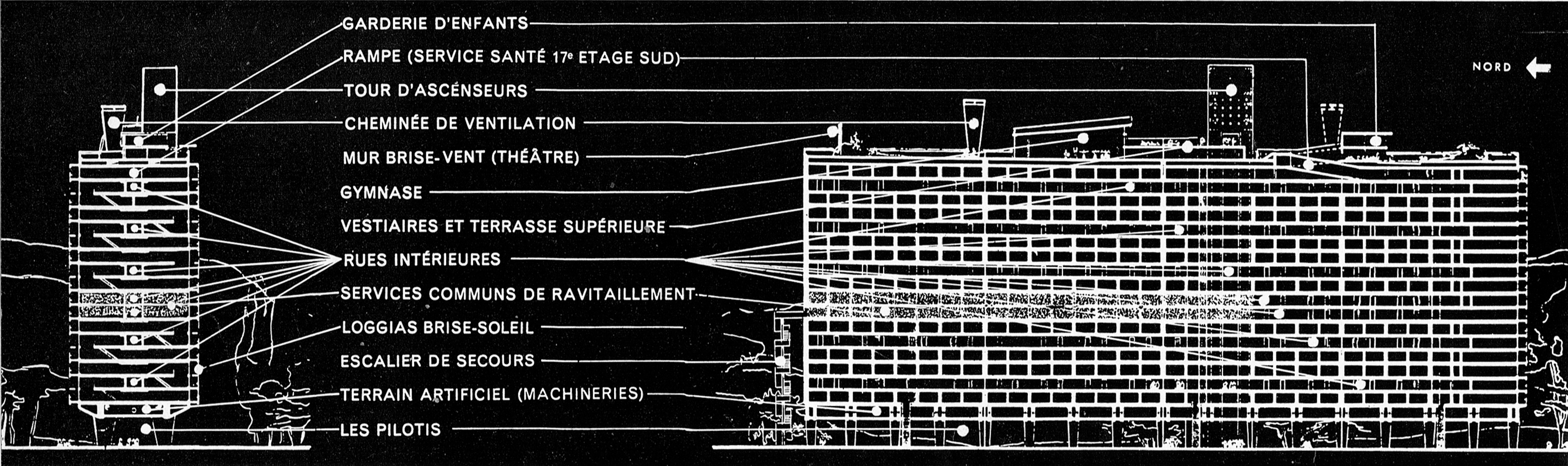

In addition to the interesting view of the apartment, the special access through the inner streets and the interesting typology of the apartments, the collective program makes the project unique. The 7th and 8th floors were designed as a small shopping center with a fishmonger, butcher, milkman, greengrocer, bakery and pharmacy. There was a laundry and cleaning service, a hairdresser and a post office. On the same floor there was also a restaurant and a hostel that could be used by residents’ guests. On the 17th and last floor was a kindergarten and daycare, connected by a ramp to the roof terrace where there is also a swimming pool for small children. The roof terrace is the most important collective space with, in addition to a garden and terrace, a gymnasium where you can also dance, a 300m athletics track and a solarium.

In a presentation to the Minister of Reconstruction and Urban Planning during the opening ceremony of the building, Le Cobusier says with a certain pride that the residents have already united in an association whose aim, among other things, is to ‘create and maintain friendly ties between residents’ and ‘organizing communal activities (social, cultural, artistic and recreational)’.

Sixty years after completion, a lot has changed. The restaurant now has a Michelin star, the guesthouses have become a hotel and many of the original shops have made way for more specialized professions such as a dentist, internet company or an architectural firm. But the community, the VvE, is still very active and, for example, still organizes the neighbors party every year. Sur le toit, on the roof. ‘Chacun apporte quelque chose a manger a partager, l’association des habitants offre les boissons’.

Le Corbusier himself called the building a Cité Radieuse, a radiant city. A building designed as a city in itself. The strength of the building is also a weakness for the city where it is located, as it completely withdraws from it. In a sense it adds nothing to Marseille, it stands alone and is at the service of its residents. With her pilotis she allows the ground level to pass beautifully beneath her, but also avoids any interaction with the city. It matches the appearance of the building, with a length of 164 m, width of 24 m, height of 56 m and a sculpturally designed roof, it is reminiscent of an important source of inspiration for the architect: the ocean liner. Ready to depart with all passengers and leave the shore amazed.

The Unité was a social housing project, realized on behalf of the French state at a time when the country was struggling with a major housing shortage just after the Second World War. The Unité was an answer to that shortage. Nakagin was a private development where all capsules were sold on the open market and the land was leased by the municipality.

Amsterdam is currently experiencing the largest housing shortage since reconstruction.During the economical crisis, too little was built, which has created a natural shortage of housing. Now that the economy is improving, even more people want to live in places that have been popular for some time, close to work, facilities and entertainment. The existing shortage and the new additional demand create an overstressed housing market that only seems to be accessible to a select number of people. Housing associations have been paralyzed by the government when it comes to the development of new construction. Fortunately, developers take their responsibility to realize commercial real estate where profit is not the only objective. It is increasingly recognized that economic value and social value reinforce each other.

Back to the question of the developer, who wants to provide a solution to the growing demand for affordable housing near the popular city centres of the Netherlands through micro-apartments. What can we learn from Kurokawa and the Unité in Marseille?

Don’t think small, think compact. And don’t stop designing. Integrate the cupboard, the kitchen and the bed (or box bed) to guarantee as much spatial quality as possible for every resident. Enable combinations between small units, creating a rich variety of apartments for a wide diversity of residents; a diversity that is characteristic of the city. Consider which functions residents can share. For example, provide laundry facilities per floor. Integrate communal functions such as a guesthouse, garden and library. Ensure that the roof of the complex can be the catalyst for connection between residents, with a swimming pool, sun deck, dining tables and fireplace. This way, residents can form a collective in a compact residential building.

Ensure that the ground floor contains a public program that is valuable to the surrounding neighbourhood, so that the building does not become a vertical gated community. Do make the building take away space from the city, but rather make it add space to it. Design osmosis – to use Kurokawa’s biological terms – where each apartment and each resident has its own identity, but can be connected to the collective and the city. This is what urban living in the twenty-first century will look like.

Sources:

Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings, Edward S. Morse (1886)

Kisho Kurokawa, Metabolism and Symbiosis, Peter Cachola Schmal, Ingeborg Flagge, Jochen Visscher (2005)

The Metabolist routine, Filipe Magalhãs en Ana Luisa Soares, Domus (May 2013)

Le Corbusier, Oeuvre complète 1946-1952, Les Editions d’Architecture Zurich

Essay published on Archined 03.02.2017

Visit project page Holon House